The epic of Gilgamesh is the oldest known. Recently made more accessible in a fresh version by Stephen Mitchell, it tells the story of an arrogant king who takes advantage of his subjects, despoils nature, and offends the gods. When his best friend dies under a god's curse, Gilgamesh seeks the secret of eternal life, hears the story of a flood that almost destroyed humankind, and finally finds, then loses a plant said to have the power of restoring youth. The story in Mitchell's version ends with Gilgamesh arriving home and describing the wonders of his great city. The ending is disappointing. It doesn't answer the key question: Does Gilgamesh grow up and change his ways? Did facing up to his friend's death and wandering in the wilderness in search of eternal life bring about some great alteration in Gilgamesh's behavior? The verses don't say explicitly. Some subtle clues suggest that, on his return, he at least has the potential for humility (sadly lacking in his early life) and a more neighborly attitude toward both his subjects and the gods. Clue #1 is how Gilgamesh reaches the "island of the blessed" where dwell his ancestor Utnapishtim and his wife, who survived the great flood. (I picture them being played in the film version by Billy Crystal and Carol Kane, reprising their roles as Miracle Max and his wife in The Princess Bride.) Gilgamesh glides down a river, uses dozens of poles to push a boat across a stagnant sea, then stands up and holds a robe so that the boat can sail the last distance. In other words, first he coasts -- which is what he's been doing all his life, and then he uses his own brawn -- still in keeping with how he has always lived. However, the other shore cannot be gained by Gilgamesh's own effort; he must allow the wind to glide the boat to its landing. In the Sumerian pantheon, the wind god is Enlil, the same god who decreed that Gilgamesh's friend, Enkidu, must die. Gilgamesh stands as a mast. A mast would come from a tree, and trees were prized in Mesopotamia as spoils of war (Roberts, 2006). (Earlier in the text, after slaying a monster, Gilgamesh celebrates his victory by chopping down all the trees in the forest that the monster was guarding.) Standing in the boat, Gilgamesh offers himself to the wind, to Enlil, as a conquered state might offer trees as tribute. When he arrives at the home of Utnapishtim, he is no longer keen to do battle, but is ready to listen to his ancient ancestor reveal the secrets of the gods. A man of action, not of words, in his early life, Gilgamesh is showing signs of change. Clue #2 is how Gilgamesh loses the magic youth-restoring plant. He lays it down while he bathes in a pool at the end of a day's traveling, and a snake smells it and carries it away, shedding its skin to show that it has been transformed (or will be, once it eats the plant). Bathing in a pool of water is also a symbol of transformation, much older than Jesus' baptism at the hands of John the Baptist. Gilgamesh is truly frustrated and sad when he dries off and realizes that his journey to the edge of the world has been in vain. But in my imagination, I can see him watching the snake's theft and deciding to do nothing about it. After all, he was having second thoughts about this "secret of youth" idea. How long would the youth last? When it wore off, would he look his actual age? Or would he still be younger, just not exactly youthful? If he ate the herb many times, would he finally turn to dust when the last dose wore off? Once the pool has revived him, he may decide that the magic plant isn't the solution after all. Clue #3 is that, at the gates of Uruk, Gilgamesh praises the beauty of Ishtar's temple, rather than railing at her, as he did earlier in the story after she propositioned him. He is no longer angry at the gods, but I don't think he feels subservient to them either. I can imagine him sprucing up the temples, as Book I of the epic describes, not as an offering, but just as one good neighbor would help out another. This change toward a less insular and more constructive attitude is supported by the text in Book XII, which Mitchell does not include in his translation. The additional material includes the story of the huluppa tree, which Gilgamesh cuts down for Ishtar, to make her a bed and a throne. Yes, he's still cutting down trees, but for a purpose, not in an emotional frenzy. Maybe he and Ishtar have both found that they need someone to talk to. Whether Gilgamesh becomes a great and wise king, I can't say, but I do see him as a changed man, more ready to listen, perhaps ready to give up bluster and arrogance for a more neighborly relationship with both the gods and his own people. As Book I relates, he finally shows some concern "for the welfare of the people and the sacred land." He has at least the potential to grow further. References: Roberts, J. (2006, July). "Centering the world": Trees as tribute in the ancient Near East. Transoxiana: Journal Libre de Estudios Orientales, 11. http://www.transoxiana.org/11/roberts-near_east_trees.html

Mitchell, S. (2004). Gilgamesh: A new English version. New York: Free Press.

Comfort for a necessary crime

Psalm 139 has taken on new meaning as I have reconsidered the concept of duality in the context of my readings on psychological development. This great hymn to God's omnipresence and omniscience contains such powerful images as in verse 8 (That God May Be Glorified):

If I climb the heavens, you are there.

If I lie in the grave, you are there.

In what grave can a living human being experience the presence of God? Psychologist Edward F. Edinger (1972) called the development of consciousness "a necessary crime" (p. 25), because at each stage, it involves a transgression that generates conflict, leading to a new level of consciousness:

What is a crime at one stage of psychological development is lawful at another and one cannot reach a new stage of psychological development without daring to challenge the code of the old stage. Hence, every new step is experienced as a crime and is accompanied by guilt, because the old standards, the old way of being, have not yet been transcended. So the first step carries the feeling of being a criminal. (p. 21-22)

To put it another way, as we become more conscious, we suffer as we sacrifice a bit of our old selves. If we do not die incrementally in this manner, we remain dependent and unable to undertake effective action in the world. Where Psalm 139 provides so much comfort is in its vision of a God whose thoughts reach out equally to those walking in the light and those hiding in darkness, even the night of their own "necessary crime." Consider verses 10-11 (The Saint Helena Psalter):

If I say, "Surely the darkness will cover me,

and the light around me turn to night,"

darkness is not dark to you;

the night is as bright as the day;

darkness and light to you are both alike.

As a longtime optimist, I am anxious about encountering the more negative aspects of my personality. Certainly, I may find untapped strengths there, but doubtless I would also encounter stumbling blocks that could hold me back. But I am assured by Psalm 139 that God will be with me throughout the process.

References:

Edinger, E. F. (1972). Ego and archetype: Individuation and the religious function of the psyche. New York: Penguin Books.

Schauble, M. (Ed.). (1998). That God may be glorified. Erie, PA: Benet Press.

The Saint Helena Psalter. (2004). New York: Church Publishing.

The Egyptian eye for nature

In his application of Jungian analysis to Egyptian civilization, Michael Rice lauds the ancient Egyptians for their skill in drawing, accompanied by their keen eye for and love of nature. It's easy to see these combined in several small limestone panels from the Freer Gallery in Washington, DC. Some panels have human images, but others show a falcon, a crocodile, and other animals, such as this bird:

Fragment: A young bird in low relief. Freer Gallery of Art, Washington, DC.

Soft limestone H: 11.0 W: 10.7 D: 1.7 cm Egypt

Gift of Charles Lang Freer, F1908.59

The description from the gallery's web page explains:

Fragments such as this one carved in low relief have been identified as "sculptor's trials" or "sculptor's models," and were used in Egypt from the Third Dynasty to Ptolemaic times. The reliefs were used to aid sculptors in instructing apprentices about the canonical Egyptian grid. The models are often "framed" by L-shaped borders, which could have been used as depth measures. The human subjects of the sculptor's models were most often idealized versions of royal heads with headcloths or uraeus crowns. The animals used in hieroglyphic writing (the alphabet and royal titularies) were most commonly modelled.

Some of the models apparently also have edges incised at regular intervals, suggesting that they could have been overlaid with a grid, and the image then used to make larger or smaller copies by working with a different size grid.

Reference:

Rice, M. (1997). Egypt’s legacy: The archetypes of Western civilization 3000-30 BC. New York: Routledge.

Image and description copyright © Smithsonian Institution.

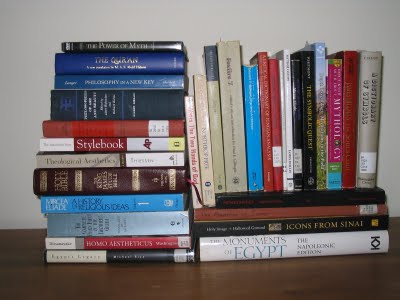

Spring 2007 Bookpile

I thought this would be fun -- pile up all the texts, research materials, and other extra readings from the three classes I just finished:

The other happy event of this week is that my 7th book on Microsoft Outlook went to press, due for release the first week in June.

End of Quarter 1

Today marks the end of my first quarter in the M.A. Humanities program at Pacifica Graduate Institute. The final papers that I turned in for my three classes are a good indicator of the breadth of this program:

Incoherence in the Cloud: Flexibility and Vitality in Social Cataloguing

The Egyptians were not confounded by their religion's proliferation of gods, overlapping iconographies, and relative lack of detailed myth stories. Likewise, the lack of an externally imposed categorization scheme need not obscure the layers of significance on a social cataloguing Web site such as del.ico.us. If there is a lesson to be learned from the balance between disorder and order achieved by the Egyptians in their religion, it is that the process of maintaining order is never-ending and requires the attention of the highest personages. Social cataloguing Web sites must invest in the work of software engineers, information analysts, and psychologists. These skilled professionals tend the temple fires behind the scenes at social cataloguing sites, constantly revising the applications that build tag clusters and other mechanisms for bringing coherence to the tag cloud.

Spiritual Rebirth Revealed: The Virgin in the Burning Bush

By combining natural vegetation with transforming flame and the sign of the divine taking on human form, the Virgin of the Burning Bush icon, a type that originated at the St. Catherine Monastery at Mt. Sinai, personifies the essential spiritual journey, in which the material world and the unseen, spiritual world may be discovered to be intertwined and interdependent. The hope and promise for each pilgrim on this journey is the possibility of being reborn as a unique and individual Self, allied with the divine wisdom and energy that powers the universe.

Identity, Fidelity, and Initiation in "The Wild Swans"

The task and trials of the heroine in Hans Christian Andersen's story The Wild Swans can be read as an extended rite of passage that concludes with her embracing a new role as wife and queen. Her success comes through the attainment of the ego strength of fidelity, described by Eric Erickson as part of his model of identity versus role confusion as the key crisis of adolescence.